As if Shakespeare wasn’t busy enough churning out histories, tragedies, and comedies by the dozen, he was also fiercely composing perfectly rhymed, tightly structured, yet deeply meaningful sonnets—154 throughout his lifetime to be exact.

Make no mistake that this is no easy task; syllable counting, rhyme scheming, and line length doesn’t always leave room for free-flowing insight. But yet, it’s The Bard, and he manages not to just pull it off, but pull it off masterfully.

Have you ever tried writing a sonnet? I have and it wasn’t pretty.

In my most recent Old School Sunday posts, I’ve been aiming to prove Shakespeare’s eternal, timeless relevance—both then and now. His ideas, his notions, come directly from the roots of human nature, and despite the many complexities and nuances of his stories and poems a very simple moral will present itself. A moral in which we all—despite time and experience—can identify.

There a various types of sonnets, which you can read about here, but the basic idea is a structured poem with stringent rules; again, like mentioned above containing a certain number of syllables (iambic pentameter), lines, and rhyme schemes. It’s an antiquated tradition that’s mainly been squashed by most of the free verse poetry (though of course even that still has its own structure) we see today.

The English (or Shakespearian) sonnet consists of fourteen lines total. Three quatrains of four lines and one two-line couplet at the end, making the rhyme scheme as follows:

abab

cdcd

efef

gg

The sonnet below is fairly well known, but it is my absolute favorite of the The Bard’s poetry for reasons I will explain later on. Read carefully though—this is not your average love poem:

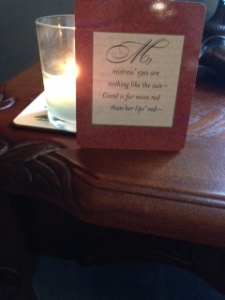

Sonnet Number 130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun—

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red—

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun—

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head:

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses I see in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound.

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet by heav’n I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

*Note: I remember from one of my college poetry classes that often, the two line couplet at the end of sonnets often seeks to disprove the preceding twelve lines. This is certainly true in Sonnet 130.

Our whole lives we hear the old adages, “No one is perfect,” or “It’s what lies on the inside that counts,” etc.

Shakespeare, it appears, beat us to this notion with Sonnet 130. In contrast to the over-romancized love poetry of his day, which often painted the object of affection as a goddess-like being, Shakespeare brought it down to the earth by saying, essentially: “Let’s be honest here. Her breath stinks, her hair’s bad, she’s tone deaf, and she’s pale. But hey, I love her anyway. There’s no one else in the world like my mistress.”

It’s a concept we sometimes tend to forget. We still look for that flawless specimen. Or worse, we expect our partners to be flawless. It’s an impossibility that no one on this planet will ever realize. Shakespeare knew it, and so should we. It may, after all, be the ticket to true love.

I can’t imagine anybody’s breath or body odor was particularly enticing back in the Bard’s day! He’s just keeping those expectations real!

LOL very true! Shakespeare was certainly ‘keeping it real.’ That’s why we love him though!

LOL. Enjoyed this post. I can always count on you for classical enrichment. Your posts take me back to the days of my mom teaching junior English and the many hours she spend studying for her masters in lit.

Thanks Melissa. Classical enrichment…love the term, I’ll take it! Your mom’s life sounds like my own life!

Great post! Couldn’t help laughing at your apt and hilarious summary of the poem. I myself love the sonnet form and wish more modern poets used it. I think the discipline of the form helps the writer to concentrate his/her ideas and images, to brush away the dross and leave only the gold. I also love the rhyme, which adds not only to the lyricism of the poem and its cadence but helps to sear the lines into the memory of the reader for easier recall. I don’t know why we don’t use more rhyme in modern poetry. Somehow it’s seen as too easy or childish or repetitive, and certainly bad rhyme, bad poetry can be that way, but so can freeform non-rhyme poetry.

Perhaps I’m just old-fashioned, but I don’t think so. I think our modern taste-makers have led us astray, and taught students and would-be poets to shun a type of poetry that has tremendous power and grace. Freeform can be wonderful, but sometimes it needs something to rein it in. It can allow us to become too lazy, undisciplined in our word choice, and sometimes that discipline can take us places we would never have imagined without that added effort. Anyway, I ramble. Sometime I’ll share my sonnet “On Sex During Finals” from back in my grad days. So much fun to write!

Thanks for your thoughtful reply, Deborah! I too, miss the old poetic form. As I teacher I often heard students say that “poetry can be anything they want it to be,” and I don’t think that’s true. I believe that widespread notion of ‘free verse’ has something to do with that–this idea that poetry is open to interpretation, etc.

And while I do think that there are some benefits to that, the ancient forms such as the sonnet gave definition to poetry, something that has gone to the wayside in recent decades. As long as the rules applied poetry actually “WAS” something. It was form to emulate, to capture. In the same way a song should have music.

I’d love to read your sonnet! Sounds great! With a title like that, who could resist?

I love that you’re aiming to prove Shakespeare’s eternal relevance. You are so right–onward!

Thanks Jessica! It’s such a strange phenomenon!

Thank you for sharing to us.this is fantastic.

Glad you like it!